The Humpback Whales

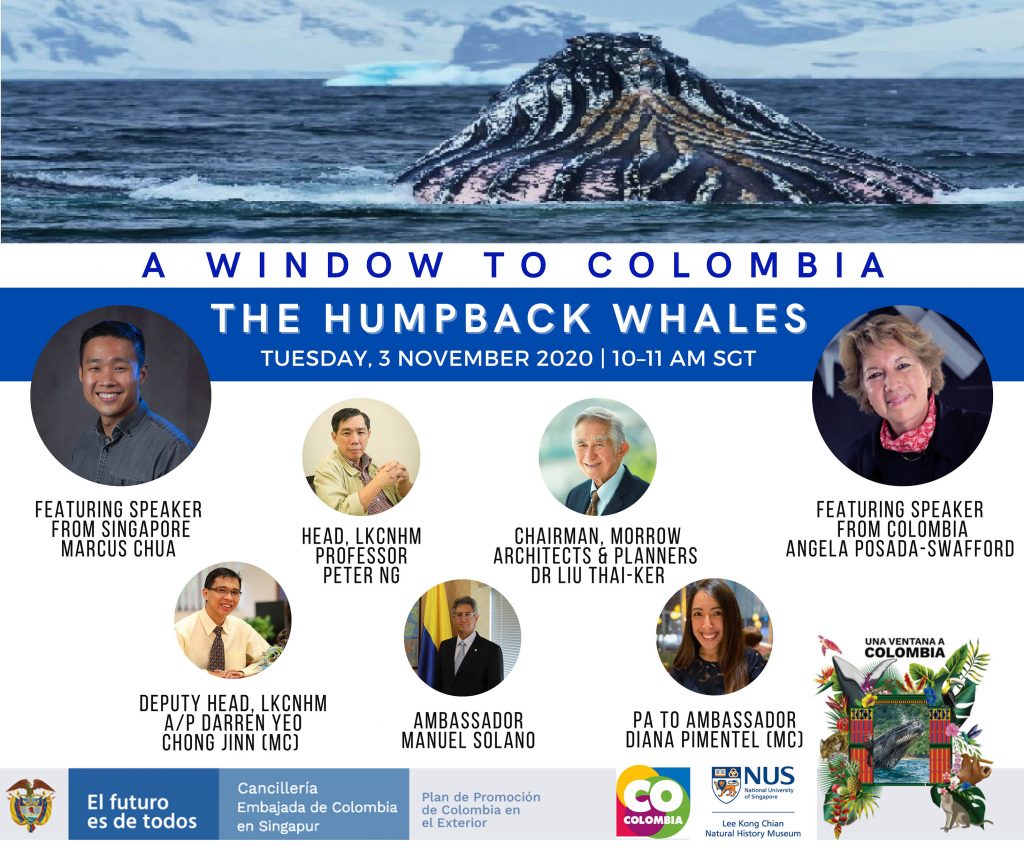

Jointly organised with the Embassy of Colombia in Singapore, the webinar ‘A Window to Colombia: The Humpback Whales’ was hosted live on Zoom on 3 November 2020.

Known for their elaborate songs that can travel across vast distances, humpback whales can be found in every ocean of the world. Sharing more about these magnificent creatures was keynote speaker and recognized science writer and journalist, Ms Angela Posada-Swafford, who once listened to the heartbeats of humpback whales from within a navy submarine!

Another cosmopolitan whale species is the sperm whale. Our mammalogist, Mr Marcus Chua, spoke about his unique experience conducting post-mortem studies on a sperm whale carcass found off Singapore’s Jurong Island in July 2015, which is now displayed in the museum gallery.

The event was also webcast simultaneously from the ARTitude Galería, with the Ambassador of the Republic of Colombia His Excellency Manuel Hernando Solano Sossa, Head of LKCNHM Professor Peter Ng and renowned architect-planner Dr Liu Thai-Ker. The webinar was hosted by Ms Diana Pimentel from the Embassy, and Associate Professor Darren Yeo Chong Jinn, Deputy Head of LKCNHM.

For more information on the event, visit here.

Question and Answer Session with the Webinar Panel

Is plastic pollution or global warming more harmful to whale populations? Is death by boat collision a frequent occurrence and serious threat to whales?

Angela: I’m inclined to think that global warming is the big umbrella or shadow that we see happening but we don’t quite yet understand it exactly. So that is the biggest threat. But perhaps the biggest threat in the shorter term is plastic pollution. Compared to boat collisions, which are surely a threat, plastic pollution is more serious and widespread issue—we even found micro-plastics buried in the ice in Antarctica.

Marcus: I agree with Angela. Both are extremely chronic problems, and the impact accumulates especially for plastic pollution. Plastics were only recorded in sperm whales starting from the 1970s, and slowly more and more plastics have been recorded in whales. It causes smaller problems such as digestive problems when ingested, but it also entangles them, resulting in drowning of whales. But in the backdrop of all these, climate change is affecting every single whale rather than individuals. The changes in temperature results in fluctuations in abundance of food and other bigger problems.

Climate change and plastic pollutions are universal problems, whereas collisions with ships is more of a localised issue, especially where there are high shipping traffic where ships and whales meet—these are the areas where the risk of collisions have to be mitigated.

Angela: To add, the boat traffic is particularly high in the North Atlantic waters. The North Atlantic right whales are among the most endangered mammals on the planet, and they are down to a few hundred individuals due to high rates of collision with ships. As whales rest, they tend to be near the surface of the water, making them vulnerable to ship strikes.

Has the changing ocean temperatures due to climate change affected or narrowed the habitats of either sperm whales or humpback whales, in terms of both habitable latitudes and depths?

Marcus: I’m not sure if there has been any conclusive studies on this as majority of whale species and populations are still recovering from the impact of historical whaling, so the impact of climate change is less clear. Models, however, predict negative future impacts on krill and all whale species.

Angela: The availability of krill as a food source is a big issue that possibly influences the whales’ habits and habitats. In general, the warming of oceans is set to change our whole planet. Here are a couple of recent papers with more details on that problem and whales:

- Albouy, C., Delattre, V., Donati, G., Frölicher, T. L., Albouy-Boyer, S., Rufino, M., Pellissier, L., Mouillot, D., & Leprieur, F. (2020). Global vulnerability of marine mammals to global warming. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 548. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-57280-3

- Derville, S., Torres, L. G., Albertson, R., Andrews, O., Baker, C. S., Carzon, P., Constantine, R., Donoghue, M., Dutheil, C., Gannier, A., Oremus, M., Poole, M. M., Robbins, J., & Garrigue, C. (2019). Whales in warming water: Assessing breeding habitat diversity and adaptability in Oceania’s changing climate. Global Change Biology, 25(4), 1466–1481. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14563

Ms Angela, when you were aboard the submarine, were there any concerns on the effects of the sonar system used for marine navigation on the whales? Was there a balance that had to be struck?

Does Colombia work with the militaries to reduce the impact on cetaceans from naval-military operations (e.g. sonar)?

Angela: Great question, and it was one that I myself asked the captain. It turns out that these submarines use what they call a “passive” sonar system. That means that they do not send in “pings”, which are loud sounds used for echolocation (unless of course they have to). Instead, for this research and for patrolling the seas, they use hundreds of hydrophones installed on the bow of the submarine to listen—like a big ear. But you are right, sounds produced by sonar arrays in other submarines and those left on the bottom of the ocean for experiments can definitely cause a lot of distress in whales. We have to think that the ocean is an opaque medium: a whale cannot see other whales very far underwater, but it can hear them. So whales rely on the sounds made by their family and mates. It is a way of saying “here I am” in the darkness of those waters.

To my knowledge, Colombia’s submarines are very silent. Some independent Colombian researchers are studying the relationship between noise pollution and the sounds of marine mammals (whales, dolphins, seals walruses, etc.) in international laboratories such as the Center for Conservation Bioacoustics at the Cornell University, providing a great source of bioacoustics and information on the natural world.

Do whales have respiratory problems? (paraphrased for clarity)

Angela: What I have read is that bacteria in the breath of whales are indicators of their state of health, as discovered in killer whales (Raverty et al., 2017).

Other sources, such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have reported last year pigmy killer whales beached in Maui with serious lung infections.

- Raverty, S. A., Rhodes, L. D., Zabek, E., Eshghi, A., Cameron, C. E., Hanson, M. B., & Schroeder, J. P. (2017). Respiratory Microbiome of Endangered Southern Resident Killer Whales and Microbiota of Surrounding Sea Surface Microlayer in the Eastern North Pacific. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 394. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00457-5

It is commonly said that when the megafauna of our oceans are disappearing, and I think it shows the severity of the issue that we are facing and it serves as a wake-up call. What are your thoughts on this?

Angela: Yes, of course. Since whales are the apex animals on top of the food chain in the oceans, if they decline it means that there is something wrong with the environment they live in (apart from issues such as hunting or collisions). When their populations are noticeably in decline, it is a wake-up call for us humans. But you know, the same is true of pollinating insects. For example, if bees disappear, our crops will be in serious trouble.

What are your thoughts on ecotourism around, for example, whale sharks? How do we balance the social benefits (increased awareness and provision of jobs) with letting wild animals stay wild?

Marcus: Whale (and other large fauna) ecotourism has brought about commercial benefits for communities and contributed to the conservation wildlife. It has also led to the realisation that these charismatic animals are worth more alive than hunted to death, which is positive for biodiversity. However, there can also be impact on the environment, hence any ecotourism model has to be conducted with ecosystem and animal welfare considerations in mind.

Angela: Good question. Just as Marcus says, ecotourism can be a double-edge sword. It all depends. I have seen ecotourism in Antarctica in action. It is the heaviest regulated activity in the whole ecotourism industry. There can only be one ship per bay at any given time, and only limited number of people can disembark to see the penguin rookeries—the penguins seemed to be ok but they also at times looked nervous. However, sometimes, in spite of the yellow tapes placed by the tour leaders to keep visitors 5 metres away from the birds, I have seen people blocking the penguin access to the sea, where they feed. I have seen penguins changing the times they feed and staying up on their colonies until their access to the sea is open again.

But tourism is inevitable. It will happen one way or the other. In that case, we must make sure that the traveller understands that they really have to be respectful of the animal. If that happens, such experiences can make even the hardest of hearts gear towards keeping our wild places intact. For example, the Antarctic cruises raises money for researchers, thanks to auctions of items on-board. And you won’t believe the money people are willing to give away for things such as the ship’s flag signed by the crew, or a lovely drawing of a whale. So it cuts both ways.

Do you think direct action conservation groups are effective? How can scientists work with conservation groups to better research on whales and other marine life?

Marcus: I am not too familiar with all that direct action conservation groups have done, but case studies show that success can be mixed because underlying issues or causes are often not addressed. There is evidence suggesting that there is sometimes a gulf between scientific findings and their application by conservation practitioners. I think the scientific community can improve this by working with these groups to better address their needs in terms of knowledge, and communication of findings. Conservation practitioners would also benefit by their willingness to change their management choices when provided with relevant scientific information.

Angela: One has to be very careful not to mix the raw emotions that sometimes these issues awake, with the rational research. I think what is effective is what has become my motto: Knowledge is power. The more you truly know about the professional and responsible research on the animal, the environment etc., the better prepared you will be to form personal opinions. My suggestion is to read, get well informed.

How do you think we can leverage more on the intersections between the Arts and marine sciences? Is the museum doing anything in this regard? How can the public be more engaged in such work, beyond outreach and citizen science?

Angela: In my experience as a science writer, journalist and communicator, I had to learn what makes you tick. In the end, a lot of it is exposing the people to the interesting side of science by doing it from a narrative storytelling angle or in a way that engages the senses, such as by anthropomorphising the subject. The crucial thing is to open a window to inspire the people to want to go beyond. Great examples are the National Geographic, the Discovery and BBC Channels.

Marcus: Earlier we were discussing about how the album (Songs of the Humpback Whale) by Roger Payne featuring acoustic recordings of the songs of humpback whales became a best-selling album in the 1970s. This is an example of how the arts have influenced science, and how studies on the bioacoustics of whales might have led to better scientific technology. In the museum, we invited artists to draw some of the specimens such as the sperm whale and other marine exhibits. This is a direct interface between the natural history museum and the arts.

Ms Angela, how has your experience following and doing research on the whales inspired your writing as a science journalist?

Angela: What a beautiful question! It has inspired me beyond what you can imagine—being in a submarine and listening to the whales for example, it really moves you. And again, it comes back to the senses (to hear, to touch and to be there). When I see that a lot of people do not have the privilege of knowing or realising that the experience can be wonderful, I am inspired to tell these stories, and look for new platforms to do so. I talk to my nephews, my friends, people in schools, to researchers and more!

I believe that we should not be thinking “us and nature”, but “us within nature”, and this message is something we need to use literary and communication weapons to put across.

How can we get Singaporeans to be interested in the wildlife of other countries, especially since we do not get to see much of the wildlife the world has to offer?

How do you recommend youths in Singapore to further their interest in marine biology in general, or whale studies specifically?

Prof Ng: If given the opportunity, exposure and knowledge that there are these wonderful natural treasures in Colombia and different parts of the world, I think many Singaporeans will be keen to explore. One other way is to share the heritage of other places, both cultural and natural heritage.

We encourage our biologists and researchers to pursue their passions in any topic. There are no boundaries, and there are many Singaporeans all around the planet. And I think this can encourage more collaborative research.

In Singapore, there are little to no opportunities on marine mammal research. Where can one get more information on the Antarctic studies collaboration?

Marcus: Closer to home, there is still a lot of be learnt about marine mammals in Singapore and Southeast Asia. We could definitely use your expertise here and in the region. Much of the studies in the Antarctic are conducted by national research outfits and academic units, so it would be best to be in touch with these directly.

Angela suggests the following links and researchers to check out for whale and marine mammal research in Colombia and Antarctica:

- Conservation International

- Fundación Omacha (Omacha Foundation)

- Ms Natalia Botero Acosta—she researches mercury concentrations in wild whales in the Colombian Pacific and Antarctica

- Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR)—for whale research and projects Antarctica