Back to Our Future: 250 Years of Observing and Documenting Nature in Singapore

In conjunction with the Singapore HeritageFest 2022

Photo Essay

Travel back in time 250 years ago, as we bring you on a journey in the form of a travel narrative which uses visual materials (including specimen photographs, maps and paintings) to illustrate some of the important points in Singapore’s natural history and why it continues to matter. Step into the shoes of renowned explorers like Christopher Smith and Isabella Bird while holding onto a chart that shows how the offshore islands of Singapore were recorded during the late 1700s. Together with the earliest extant natural history specimens collected from Singapore in the 1790s, you will understand the efforts taken to catalogue and categorise the island’s natural heritage through observations, drawings and specimens. With this context in place, visual materials of some important and iconic animals, plants and areas in Singapore are used to illustrate the natural heritage of the island.

It is the year of travel. After over two years of being on a small-ish island, we’re all ready to pack our bags, buy our tickets, book accommodation and to start posting on social media.

But before you leave our sunny island, we’d love for you to join us on a journey through some familiar bits of Singapore – but one that takes us across time into lesser-known waters, if you will – to (re)discover our natural heritage.

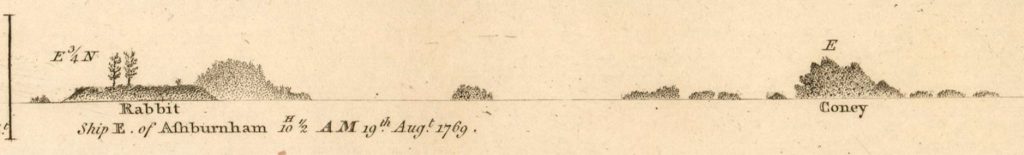

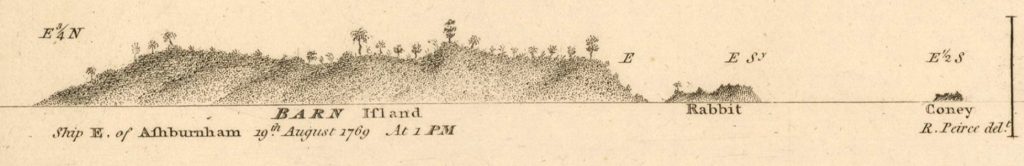

We begin with a most unconventional record of travel along Singapore’s familiar southern coast but very deep in time. Blink. Open your eyes. It’s 10:30 am on 19 August 1769 and we’re aboard the ship ‘Ashburnham’ as we encounter the Rabbit, the Coney and Barn Island. Next to us, a member of the crew is making sketches of these and the many other islands and islets around Singapore as the ship sails past.

What the ship ‘Ashburnham’ saw as it sailed past the Rabbit (Pulau Biola), the Coney (Pulau Satumu) and Barn Island (Pulau Senang) between 10:30 am and 1:00 pm on 19 August 1769 (Source: Gallica / BnF)

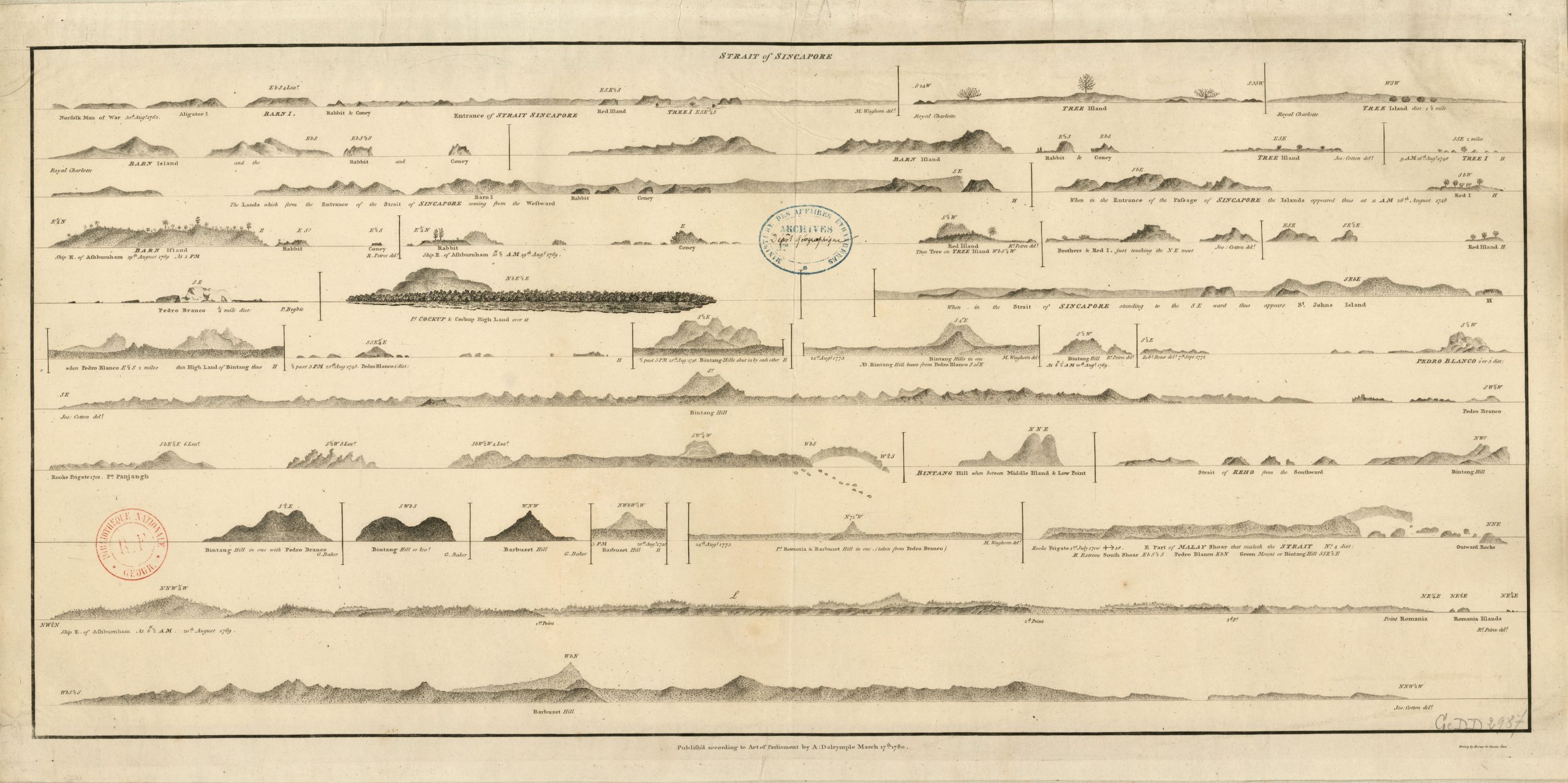

These sketches would be included in a 1780 chart entitled ‘Strait of Sincapore’ (the spelling used on the chart).

Sketches of the many islands and islets around Singapore made during voyages in the 1700s (Source: Gallica / BnF)

Accompanying such charts would be sailing directions like this one from 1805 telling you that “if the night is not very dark, either Barn Island or St. John will be visible, and when mid-way between them, both at the same time. As a guide use the south end of either of these islands, whichever is most conspicuous”. If this was read with a computer voice, we have the makings of an early version of Waze or Google Map.

This is Singapore in the distant past, before Barn Island becomes Pulau Senang, the Rabbit becomes Pulau Biola, and the Coney becomes Pulau Satumu (aka Raffles Lighthouse).

Besides the people we encountered on the ‘Ashburnham’, what else are these travellers up to? Do they collect and bring things home with them? Most certainly! This is where Barn Island plays a starring role. It is where the earliest known extant natural history material as well as a glimpse of some of our earliest natural heritage comes from.

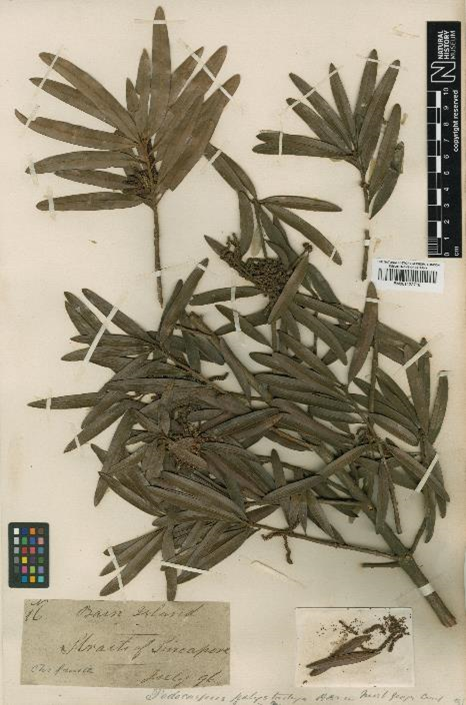

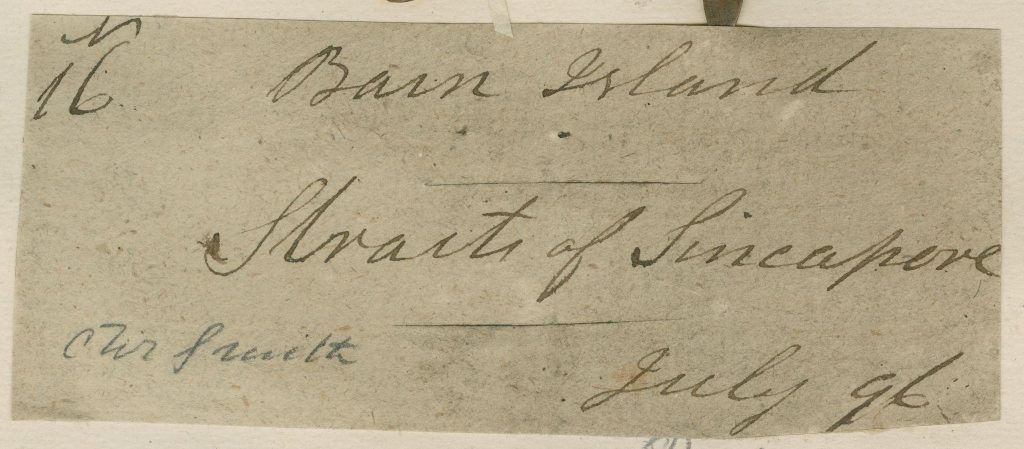

Here we come to the enigmatic botanist and plant collector Christopher Smith. Blink. Open your eyes. We land on Barn Island with Smith. He has just arrived from Prince of Wales Island (Penang) after his travel plans went awry when he missed his boat six days ago. Seizing the opportunity, he has come to Barn Island to collect plants. While we watch him, he collects seven plants which he will later send back to England. We see that one of them is a stalk from ‘jati laut’ or sea teak (Podocarpus polystachyus). On a slip of paper, he writes: “Barn Island / Straits of Sincapore / July 96”. The year is 1796.

The ‘jati laut’ or sea teak (Podocarpus polystachyus) specimen from Barn Island (Pulau Senang) collected by Christopher Smith in July 1796, and a close-up view of the label from the bottom right corner. The specimen now resides in the Natural History Museum in London (Source: Natural History Museum)

This plant specimen – one of seven – will come to rest in the Natural History Museum in London where it remains two-and-a-half centuries after it left Barn Island. These are the earliest natural history specimens from Singapore known to have survived the vagaries of time and other specimen-destroying occurrences such as pests and war. When taken together with the sketches of Barn Island in the 1780 chart, we get a fuller picture of a very different Singapore – we see not just the islands but also the plants that grew on them. If the past is a different country, then the sketches and the plant specimens are like postcards from an acquaintance we’ll never meet.

We now turn to Stamford Raffles and his sometimes-not-so-merry band of naturalists. Blink. Open your eyes. It’s June 1819 and we’re with Pierre-Médard Diard, Alfred Duvaucel and William Jack, the three European naturalists – there were certainly many other unnamed local collectors – working with Raffles during the first Singapore biodiversity expedition. During this expedition, the first animal (a sponge) and the first bird from Singapore to be given their scientific names are collected.

We first go to a forest with these collectors. It will come to be known as Macritchie to future generations. Up in the trees above is a bird with feathers on its head that can look like an umbrella all decked out in brilliant green plumage. The naturalists collect a specimen which is immortalised in this drawing which accompanies its scientific description and name (Calyptomena viridis) in a text that will be published on 25 July 1822.

The illustration of the green broadbill (Calyptomena viridis) that accompanied the earliest scientific description and naming of this species. (Source: Biodiversity Heritage Library)

Next, we are aboard a boat dredging for specimens under the sea. The other ‘first’ during this period is collected – a marine sponge commonly known as Neptune’s cup (Cliona patera). The naturalists are clearly in a very jovial mood, and Raffles goes so far as to use these specimens to toast their discoveries: “Our entertainment was truly marine; for we had on the same day discovered those Neptunian sponges … which served us as goblets”. (He also eats a dugong – but that’s a story for another time.)

The first known depiction of the Neptune’s Cup (Cliona patera) (left) and a specimen of the sponge mounted on a wooden plinth (right) (Sources: Biodiversity Heritage Library [left]; Tan Heok Hui / LKCNHM [right])

Raffles and his company are not the only travellers to find Singapore’s waters beguiling. Blink. Open your eyes. Standing beside us as we lean over the railing of a steamship just outside the harbour is Isabella Bird, one of the first female explorers of her time. She will become famous for her book ‘The Golden Chersonese and the Way Thither’. It’s a sweltering Tuesday, the 19th of January 1879. She remarks that “it is hot–so hot!”.

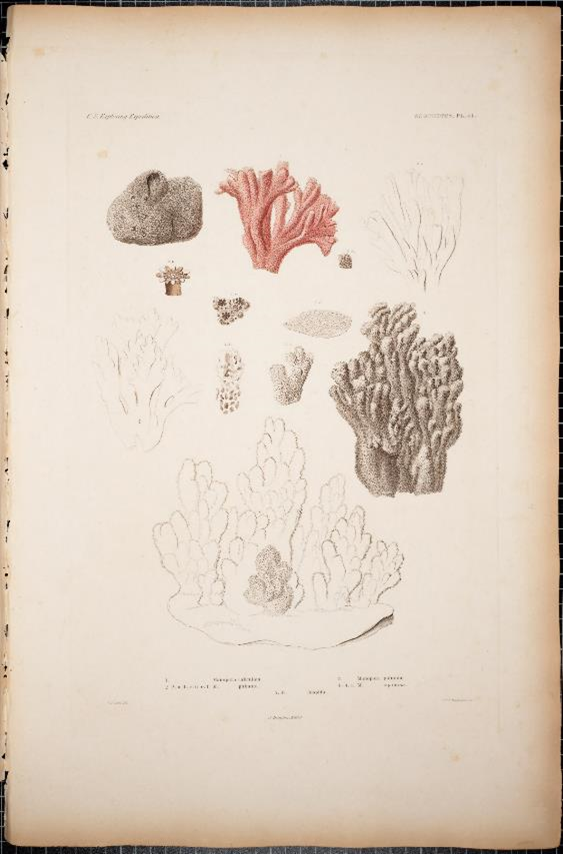

Notwithstanding the heat, she’s beguiled by the marine life she sees. She writes how “the clear depths of aquamarine water” are filled with “forests of coral white as snow, or red, pink, violet, in massive branches or fern-like sprays” surrounded by “fish as bright-tinted as themselves flash … like ‘living light’”. Years before Bird’s visit, the United States Exploring Expedition visited Singapore in 1842 and collected coral specimens which were some of the earliest to be illustrated and became the first from the island to be named scientifically. These drawings offer us a hint of what Bird saw.

A plate depicting the illustrations of the coral specimens collected during the United States Exploring Expedition in 1842 (Source: Biodiversity Heritage Library)

Sadly, as beautiful a marine environment as Bird describes, we are witnessing the beginnings of the large-scale collecting of plants and animals for sale. The corals and other marine animals that we see have actually been collected – “fresh from their warm homes beneath the clear warm waves” – ready for sale to travellers.

Blink. Open your eyes. We are at Pulau Ubin where we will dwell for a while and eventually close our journey together. Up in the trees above is a bird with feathers on its head that can look like an umbrella all decked out in brilliant green plumage. Someone we’re with writes the day’s date in a notebook to record the observation – the year is 1941. This is the last known sighting of the green broadbill in Singapore for decades to come. The first bird from Singapore to be given a scientific name is no longer found in its original locality. By now the Neptune’s cup is also already extinct because it is in demand by museums for display and collectors of curios. Such losses are repeated in the decades ahead. Forests are cleared. Islands reclaimed. You feel like you should close your eyes now, dreading what comes next.

It’s OK. You can open your eyes. There is reason for cheer. Chek Jawa is spread out before us. This corner of Pulau Ubin is a haven for coastal biodiversity – a unique convergence point where several important natural habitats meet to become home for an abundance of wildlife, rare plants and migratory birds. And on this day – 14 January 2002 – the decision has just been made to preserve this wetland treasure for locals to enjoy and more discoveries of new species to be made. The place where the last green broadbill was sighted has now become an “outdoor classroom”. This decision signals a heartening shift towards a better appreciation of Singapore’s natural heritage – one that needs to be preserved for the future, as well as the continued need for hard work to preserve and care for what we have.

Blink. Open your eyes. We are almost at our journey’s end. You look up and see our familiar feathery friend, the green broadbill. The year is 2014. This bird is beginning to once again make Singapore its home.

Blink. We’re back home safely in 2022. On 25 July 2022, it will have been exactly two centuries since the green broadbill was given a scientific name – the recognition that it is one of the multitudes of unique species that share our island home.

With its co-travellers, this island has made a remarkable journey through time: there were the original inhabitants, the animals and plants; visitors like the crew aboard the ‘Ashburnham’, the naturalists in 1819 and Isabella Bird; and now we have the privilege of sharing in this sojourn. We hope you enjoyed this journey together, and that it will inspire you to have a greater curiosity for our natural heritage and in turn become better co-travellers on this adventure!