ABYSS 2020: Field Notes in Isolation & an Expedition

Written by Iffah Binte Iesa (Curator of Cnidarian, Echinoderm & Microscope Slide Collections) on her experience on-board the 37-day expedition to the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) in the Pacific Ocean from February–March 2020 as part of the Keppel-NUS Corporate Laboratory’s research team.

Long ago before the Great Clock, time was measured by changes in heavenly bodies: the slow sweep of stars across the night sky, the arc of the sun and variation in light, the waxing and waning of the moon, tides, seasons. Time was measured also by heartbeats, the rhythms of drowsiness and sleep, the recurrence of hunger, the menstrual cycles of women, the duration of loneliness.

—Einstein’s Dreams, by Alan Lightman

Field Notes?

12 Feb 2020, Panama: On board vessel at 6PM.

13 Feb 2020, Panama: Still berthed. Lab orientation. Priority is managing space. Understand arrangements among stakeholders. Ensure communication of equipment and material distribution. Establish baseline expectations and use of equipment. Optimise workflows based on equipment limitations. Chemical preparations. Learned some words in other languages (Cantonese, French and Spanish) from colleagues of other nationalities.

14 Feb 2020, Panama: Shifts began for meals. Still anchored. Emergency drill at 5PM. Muster station through 6th floor. Life jackets, roll call. Life raft orientation. Ice cream cake at lunch; it’s someone’s birthday. Group photo.

Front row (from left): Dr. Bharath Kalyan, Ms. Lara Zalena Kamal (Keppel Technology & Innovation), Ms. Iffah Iesa, Dr. Pauliina Rajala (SCELSE, NTU) and Ms. Inès Barrenechea Angeles (University of Geneva).

15 Feb 2020, day 1 of transit to site: Sunrise at the bow— it’s hard to breathe with the wind in face. 10.30AM RC01 meeting. After lunch, Science meeting. Tea time with TMSI folks; tuna, cracker & bacon/caviar pastes. (edit: those pastes are the Captain’s jam.)

16 Feb 2020, day 2 of transit to site: Time retarded 1 hour, meal time stays the same. Did some work, got chased out of conference room. Gym with Cheah Hoay and Sam. Sea sick. Ate Cheetos; it helped. Tom yum at lunch (edit: tom yum at dinner too). 2PM: Swee Cheng gave orientation for SLR camera and microscope use. Prepared chilled ethanol. Process details meted out. Science talks at 4PM. Stargazing with Ines and Robert (night shift).

17 Feb 2020, day 3 of transit to site: Clock retards another hour at 2PM. Breakfast with CCH, ST and Pauliina. Pauliina’s favourite group of microbes is the methanogenic archaea. In bed all day?

18 Feb 2020, day 4 of transit to site: Dry run with full Geology and Biology team, meeting at 1PM. Slept on time to prepare for night shift.

19 Feb 2020, day 5 of transit to site: Woke up at 2AM. Sunrise at 4.30AM. Lunch at 5.30AM. First day of period. Prepare for cramps. 11AM meeting, 1PM meeting.

21 Feb 2020, day 7 of transit to site: Last “free” day. Helped Pauliina with pressure gauge. Printed and laminated protocols. No more working in the lounge. Hammering works at 7AM and 7PM. Remember evacuation route, remember offshore training.

22-23 Feb 2020, CCFZ box core 001: Shift changed at 11.30PM. Nodules cleared, mud to be sliced. Sieving needs refinement. 60+ sponge individuals; amazing. Tanaid, copepod, isopod, Nausithoe, polychaetes. Prepared for next shift. Work ended: 5.40AM (23 Feb 2020). Science meeting: Bathymetry information – ridge/ plateau?; Nodules crumbly; Biologically active.

24-25 Feb 2020, CCFZ box core 003/004: No specimens to process for 003. To wait for next deployment. Handed over in lab van approx. midnight. Labelled cryogenic vials. Accounted. Discrepancies? To check with Shift 2. Box core 004 down 6.30AM, ETA/R/D 10.30AM.

26 Feb 2020: Did not get to eat the cake for breakfast (supper?). Handed over in van 11.50PM. Unsorted materials. Took photographs, preserved them. Labelled specimens and arranged cryo box. Backed up photographs, keyed data into excel. Ate small meals. Handed over.

1 Mar 2020: Only completed 90% of sieving. Handed over last bucket to day shift (5–10cm). Carnivorous sponge. No Plenaster. Busy, feels good.

2 Mar 2020: 5 box cores back-to-back in 24h.

3-4 Mar 2020: Time went by so fast. Day’s over?

8 Mar 2020: Slow day, rest day. Went to van with Cheah Hoay. Finished keying in excel. Backed up CH’s hard disk. Slept till 8AM (1 hour). Time changes again tonight to Anchorage Alaska. How does time really work?

The nights went by in blinks when there were box cores to process. My field notes became increasingly hard to decipher over the course of the research cruise. Sometimes I wrote in codes only the past version of me would understand. Shift after shift, lull time after lull time, box core after box core, one instruction after another, constantly adjusting time differences and daily processes. Many unprecedented events occurred; amidst peace, bursts of activity littered the expedition timeline and participants coped accordingly with adequate communication and attempted reassurance.

Compared to other experienced seafarers and scientists aboard, with hundreds of days of sea life under their belts, I was a greenhorn guest at sea. I learned first-hand that many unimaginable things could go wrong out there, isolated from the rest of the world for a mere 37 days at sea (46 days away from Singapore and 60 days away from home).

Where regrets were had, they were fleeting. I was always looking forward to the next box core.

When a successful sample emerges from the abyssal depths, after the layer of top water has been drained into a fine-mesh sieve, in a glance you might not see anything interesting at all. But as with approaching other topics in life, it is important to be reminded that “things are not always what they seem,” especially with our limited senses. Only with careful and methodical examination using tools such as microscopes can many of the organisms be visible to us. The biological team collected various sub-samples of sediment to study the microbes, foraminiferans, meiofauna, macrofauna and megafauna.

Eye-opening Forams

Foraminifera can be found in almost all the oceans in the world. They are single-celled organisms characterized by having a shell/test surrounding the fluid-filled body, with one or more chambers. Some of them utilise materials from the environment to assemble their intricate and delicate tests. They can range from being as small as 100 micrometres to a few centimetres in size.

Personally, it was thrilling to observe the processes of identification and researchers brimming with excitement over unassuming blobs and minute organisms only observable under microscopes. To learn of the details on what is known or unknown, and what is unknown about the known.

A Jelly Good Time

Many jellyfish (in phylum Cnidaria) undergo both sexual and asexual reproduction. Complexities and variations in their life cycles have been intriguing subjects for researchers and aquarists alike. Be it for identification of species or advancing jellyfish husbandry for aquariums, the beautiful free-living medusa stage of jellyfishes is popularly sought after and reared. Generally less featured are the immobile (sessile) polyps or attached stages of the jellyfish’s life cycle.

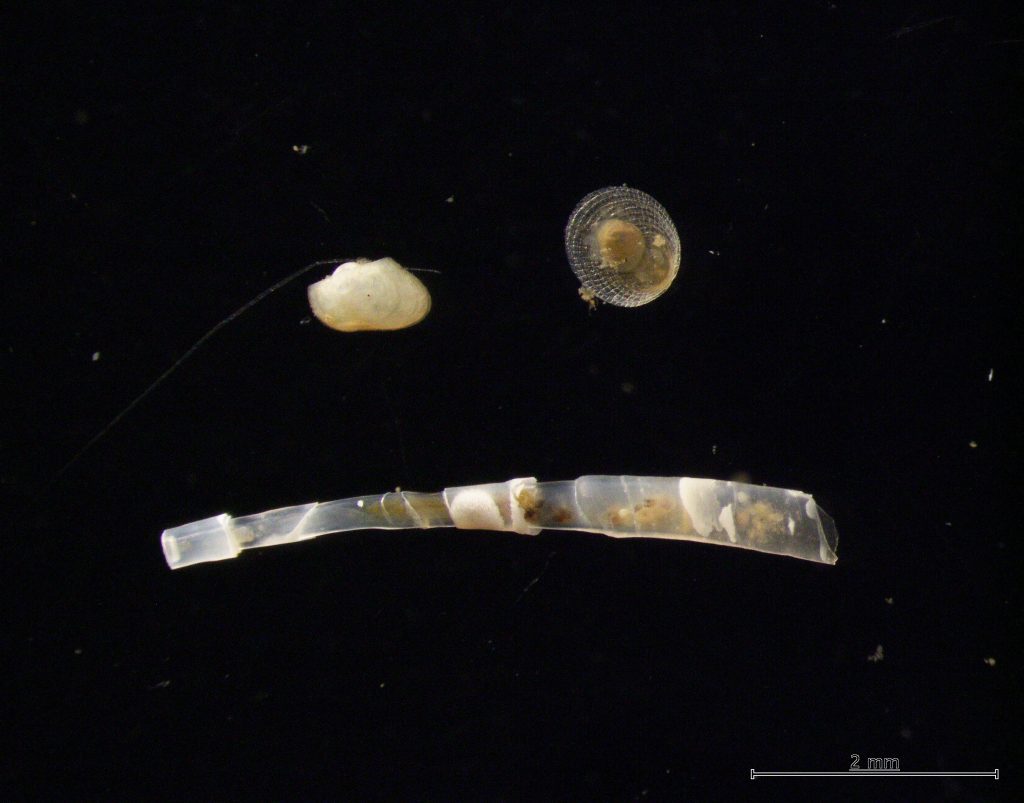

This deep-sea polyp collected belong to the medusozoan order Coronatae. Genetic material from similar polyps collected from the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone (CCZ) in a Dahlgren et al. 2016 study places the jellyfish identity provisionally as Nausithoe sp.

Unlike jellyfishes from other orders (Rhizostomeae or Semaestomeae) which have relatively flexible, gelatinous overall appearance in their polyp stage, the coronate polyp has a stiff, unique two-layered tube. The exoskeleton seems to outlast their occupants, and empty tubes also serve as a refuge for other organisms like foraminifera. The rigid surface of these polyps can also serve as substrate for other sessile organisms to settle on.

Molluscan Foot (Notes) & More

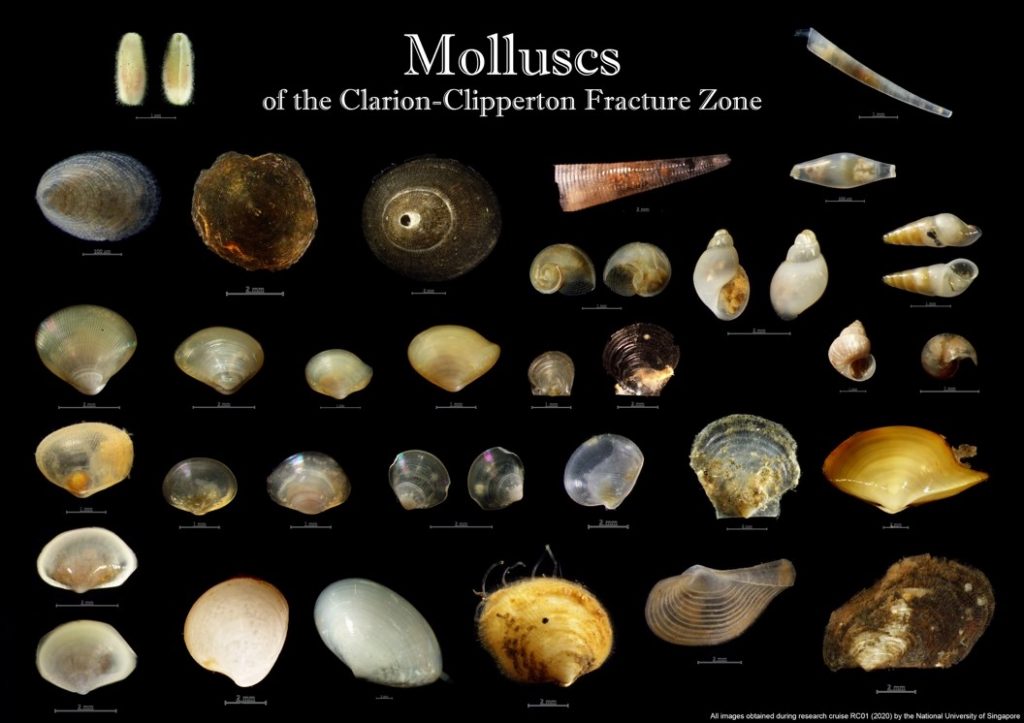

While not as abundant as foraminifera or cnidarian polyps, molluscs were common during the live sorting of fauna on the seabed surface of the box core sample. It was particularly satisfying to realise that in the span of five weeks, samples across all seven orders of molluscs were found. This includes Gastropoda, Bivalvia, Aplacophora, Monoplacophora, Polyplacophora, Scaphopoda and Cephalopoda (mainly squid beaks found during sorting).

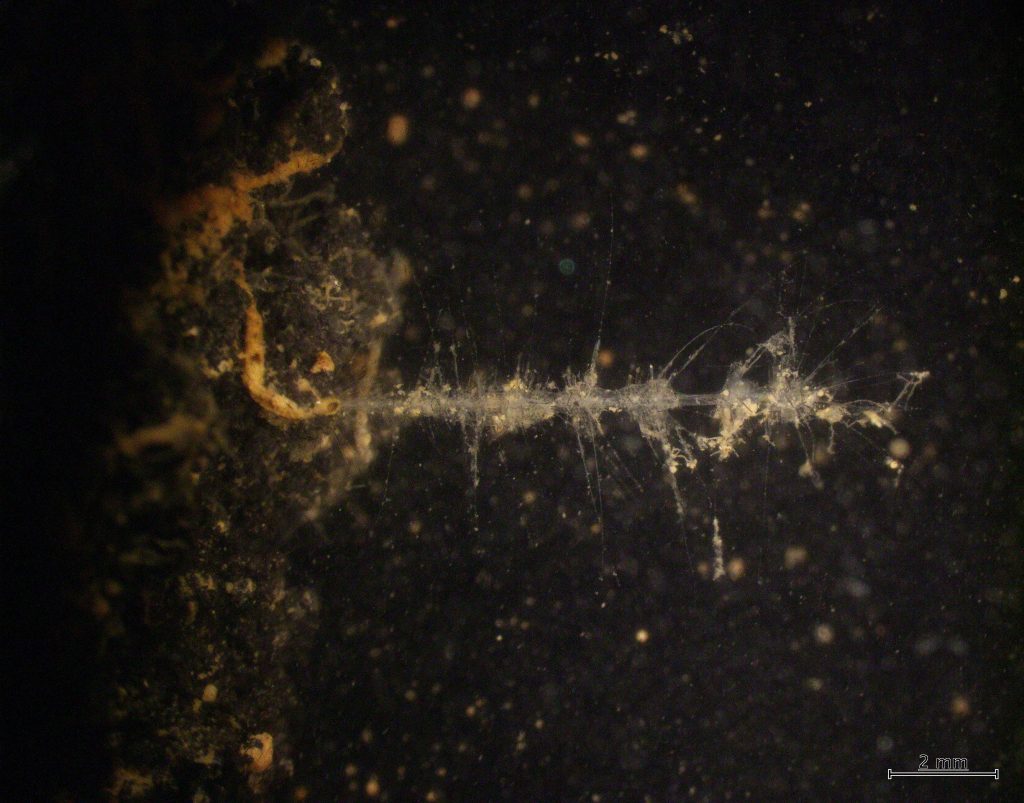

During the cruise, my interest level in marine sponges spiked— there were so many different forms of these found on the polymetallic nodules enthusiastically highlighted to me by TMSI colleague Lim Swee Cheng. From blob-shaped, more robust, filter feeders to delicate carnivorous sponges that use long filaments to trap other animals as prey (see Vacelet 2007), sponges found in the deep-sea were fascinatingly diverse.

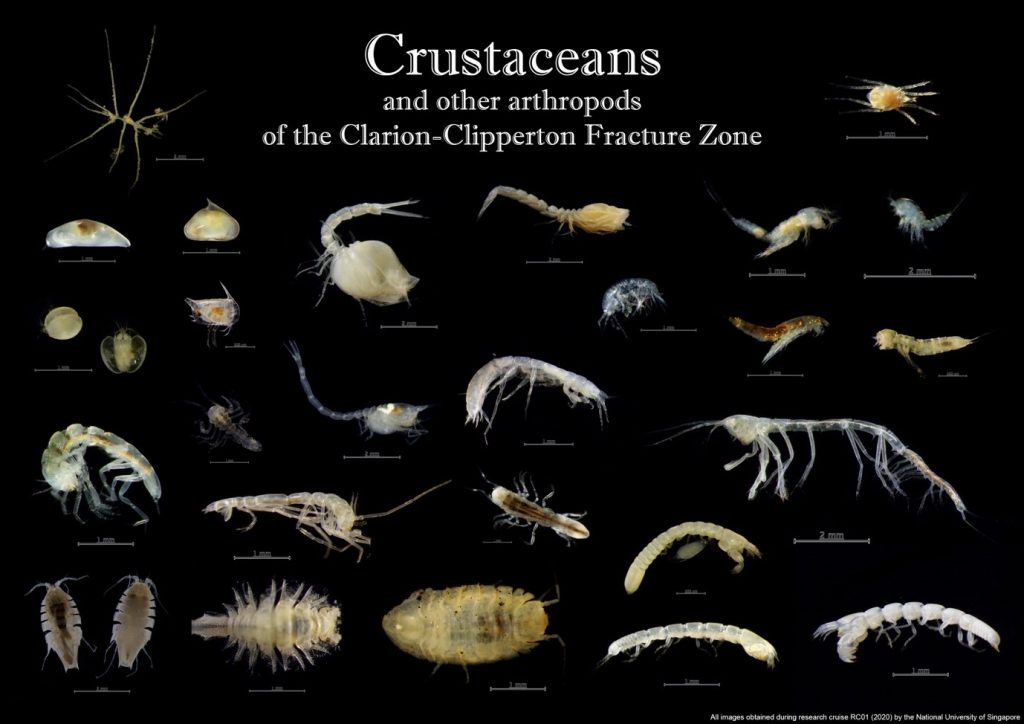

Other faunal subjects of interest had a little more character and appendages—crustaceans! Some specimens are new to science and the presence of some species potentially clarifies geographical and/or bathymetrical boundaries of species’ known distribution. The diversity and abundance of crustaceans in the deep-sea raise fundamental questions about their ecological importance and specific functions. From an earlier expedition to the Pacific Ocean in 2015, new species of tanaids were collected and it will not be surprising if more were collected from the recent CCZ sampling.

The End of an Anomalous Normalcy

The length of the expedition and being out at sea may not be much if measured typically by the number of days. Time on the expedition to the CCZ was instead measured by the sunrises we caught, super moons observed, stars counted, number of box cores, photographs taken, scientific discoveries made, potential future collaborations discussed and the tense moments in the face of an unpredictable future. And that time, in experience, was significant.

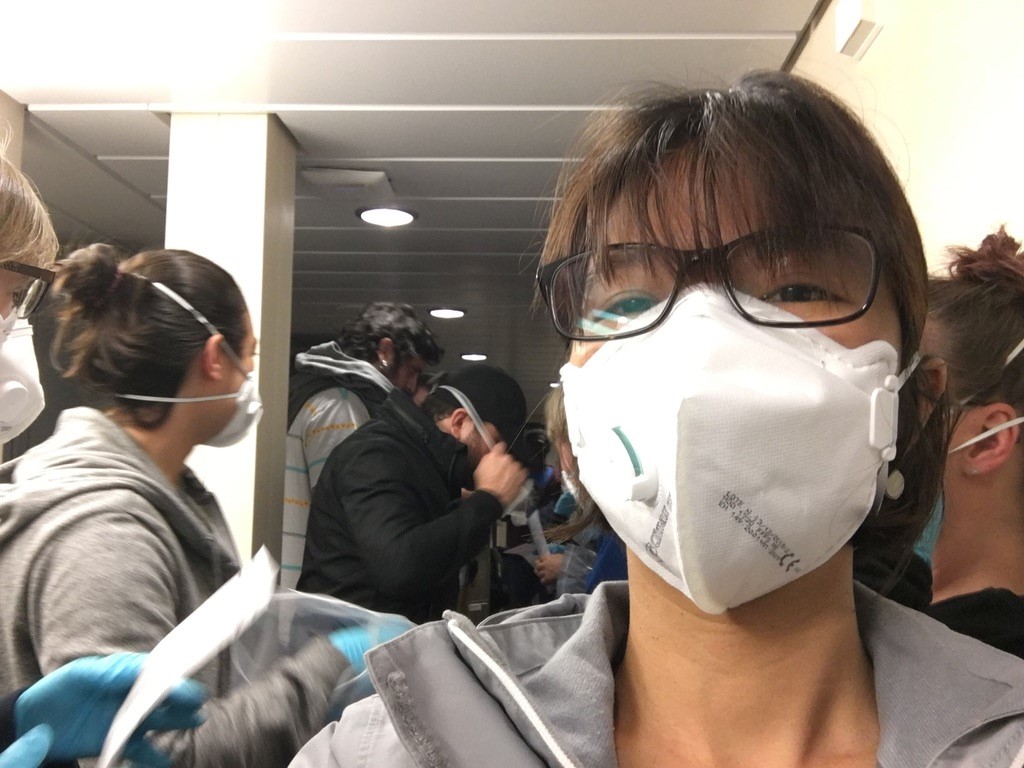

Little did the team know that our anomalous stint on the vessel in the middle of the Pacific Ocean was our last taste of a “normal” life. Tested were our nerves, patience and resilience as several curveball situations swerved our way. When the expedition came to a sudden halt, several flight bookings were cancelled as more countries’ borders closed and difficulties in risk management due to volatile current affairs emerged… the physical isolation did not help. Nevertheless, the tenacity of the organisers, agents, ship’s crew and expedition participants triumphed over the challenges.

A personal favourite example was when safety kits were swiftly put together: the ship’s stock of masks were generously distributed, leftover ethanol and glycerol for specimen preservation were used to prepare hand sanitisers in 50 ml tubes and nitrile gloves from the laboratories’ supply were given to everyone as we prepared to brace a different world on land. I will always be grateful to have witnessed the empathy and versatility of the crew.

Isolation is not a novel concept to many of us. Depending on the research question, to many field researchers and naturalists, the more secluded a survey site is (away from civilization), the better. Of course, neither is the concept entirely new to many of us who spend time alone consumed in work and crippling thoughts in sudden country-wide lockdowns. Some thrive, some deride, some cope. I comply and hope we do not forget too quickly our lessons in confinement.

Undeniably though, my most wonderful memories of museum work were made in isolation. Whether it was deep in the forests, bobbing in the middle of oceans, diving in caves or in the dark… being cut off from the world and its mundanities (in one way or another) has given me irreplaceable, deeply etched memories.

How long more would it be before we can continue our adventures in isolation and field science like before?